American Anthropology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

American anthropology has

American anthropology has

Nevertheless, the term "culture" applies to non-human animals only if we define culture as any or all learned behavior. Within mainstream physical anthropology, scholars tend to think that a more restrictive definition is necessary. These researchers are concerned with how human beings evolved to be different from other species. A more precise definition of culture, which excludes non-human social behavior, would allow physical anthropologists to study how humans evolved their unique capacity for "culture".

Chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'' and ''Pan paniscus'') are humans' (''Homo sapiens'') closest living relatives; both are descended from a common ancestor which lived around seven million years ago.

Nevertheless, the term "culture" applies to non-human animals only if we define culture as any or all learned behavior. Within mainstream physical anthropology, scholars tend to think that a more restrictive definition is necessary. These researchers are concerned with how human beings evolved to be different from other species. A more precise definition of culture, which excludes non-human social behavior, would allow physical anthropologists to study how humans evolved their unique capacity for "culture".

Chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'' and ''Pan paniscus'') are humans' (''Homo sapiens'') closest living relatives; both are descended from a common ancestor which lived around seven million years ago.

The kind of learning found among other primates is "emulation learning," which "focuses on the environmental events involved – results or changes of state in the environment that the other produced – rather than on the actions that produced those results."Michael Tomasello 1990 "Cultural Transmission in the Tool Use and Communicatory Signaling of Chimpanzees?" in ''"Language" and Intelligence in Monkeys and Apes: Comparative Developmental Perspectives'' ed. S. Parker, K. Bibson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 274–311 Tomasello emphasizes that emulation learning is a highly adaptive strategy for apes because it focuses on the effects of an act. In laboratory experiments, chimpanzees were shown two different ways for using a rake-like tool to obtain an out-of-reach-object. Both methods were effective, but one was more efficient than the other. Chimpanzees consistently emulated the more efficient method.Nagell, K., Olguin, K. and Tomasello, M. 1993 "Processes of social learning in the tool use of chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'') and human children (''Homo sapiens'')" in ''Journal of Comparative Psychology'' 107: 174–186

Examples of emulation learning are well documented among primates. Notable examples include Japanese

The kind of learning found among other primates is "emulation learning," which "focuses on the environmental events involved – results or changes of state in the environment that the other produced – rather than on the actions that produced those results."Michael Tomasello 1990 "Cultural Transmission in the Tool Use and Communicatory Signaling of Chimpanzees?" in ''"Language" and Intelligence in Monkeys and Apes: Comparative Developmental Perspectives'' ed. S. Parker, K. Bibson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 274–311 Tomasello emphasizes that emulation learning is a highly adaptive strategy for apes because it focuses on the effects of an act. In laboratory experiments, chimpanzees were shown two different ways for using a rake-like tool to obtain an out-of-reach-object. Both methods were effective, but one was more efficient than the other. Chimpanzees consistently emulated the more efficient method.Nagell, K., Olguin, K. and Tomasello, M. 1993 "Processes of social learning in the tool use of chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'') and human children (''Homo sapiens'')" in ''Journal of Comparative Psychology'' 107: 174–186

Examples of emulation learning are well documented among primates. Notable examples include Japanese

The kind of learning characteristic of human children is imitative learning, which "means reproducing an instrumental act understood intentionally." Human infants begin to display some evidence of this form of learning between the ages of nine and 12 months, when infants fix their attention not only on an object, but on the gaze of an adult which enables them to use adults as points of reference and thus "act on objects in the way adults are acting on them." This dynamic is well documented and has also been termed "joint engagement" or "joint attention." Essential to this dynamic is the infant's growing capacity to recognize others as "intentional agents:" people "with the power to control their spontaneous behavior" and who "have goals and make active choices among behavioral means for attaining those goals."

The development of skills in joint attention by the end of a human child's first year of life provides the basis for the development of imitative learning in the second year. In one study 14-month-old children imitated an adult's over-complex method of turning on a light, even when they could have used an easier and more natural motion to the same effect. In another study, 16-month-old children interacted with adults who alternated between a complex series of motions that appeared intentional and a comparable set of motions that appeared accidental; they imitated only those motions that appeared intentional. Another study of 18-month old children revealed that children imitate actions that adults intend, yet in some way fail, to perform.

Tomasello emphasizes that this kind of imitative learning "relies fundamentally on infants' tendency to identify with adults, and on their ability to distinguish in the actions of others the underlying goal and the different means that might be used to achieve it." He calls this kind of imitative learning "cultural learning because the child is not just learning about things from other persons, she is also learning things through them — in the sense that she must know something of the adult's perspective on a situation to learn the active use of this same intentional act." He concludes that the key feature of cultural learning is that it occurs only when an individual "understands others as intentional agents, like the self, who have a perspective on the world that can be followed into, directed and shared."

Emulation learning and imitative learning are two different adaptations that can only be assessed in their larger environmental and evolutionary contexts. In one experiment, chimpanzees and two-year-old children were separately presented with a rake-like-tool and an out-of-reach object. Adult humans then demonstrated two different ways to use the tool, one more efficient, one less efficient. Chimpanzees used the same efficient method following both demonstrations, regardless of what was demonstrated. Most of the human children, however, imitated whichever method the adult was demonstrating. If the chimps and humans were to be compared on the basis of these results, one might think that chimpanzees are more intelligent. From an

The kind of learning characteristic of human children is imitative learning, which "means reproducing an instrumental act understood intentionally." Human infants begin to display some evidence of this form of learning between the ages of nine and 12 months, when infants fix their attention not only on an object, but on the gaze of an adult which enables them to use adults as points of reference and thus "act on objects in the way adults are acting on them." This dynamic is well documented and has also been termed "joint engagement" or "joint attention." Essential to this dynamic is the infant's growing capacity to recognize others as "intentional agents:" people "with the power to control their spontaneous behavior" and who "have goals and make active choices among behavioral means for attaining those goals."

The development of skills in joint attention by the end of a human child's first year of life provides the basis for the development of imitative learning in the second year. In one study 14-month-old children imitated an adult's over-complex method of turning on a light, even when they could have used an easier and more natural motion to the same effect. In another study, 16-month-old children interacted with adults who alternated between a complex series of motions that appeared intentional and a comparable set of motions that appeared accidental; they imitated only those motions that appeared intentional. Another study of 18-month old children revealed that children imitate actions that adults intend, yet in some way fail, to perform.

Tomasello emphasizes that this kind of imitative learning "relies fundamentally on infants' tendency to identify with adults, and on their ability to distinguish in the actions of others the underlying goal and the different means that might be used to achieve it." He calls this kind of imitative learning "cultural learning because the child is not just learning about things from other persons, she is also learning things through them — in the sense that she must know something of the adult's perspective on a situation to learn the active use of this same intentional act." He concludes that the key feature of cultural learning is that it occurs only when an individual "understands others as intentional agents, like the self, who have a perspective on the world that can be followed into, directed and shared."

Emulation learning and imitative learning are two different adaptations that can only be assessed in their larger environmental and evolutionary contexts. In one experiment, chimpanzees and two-year-old children were separately presented with a rake-like-tool and an out-of-reach object. Adult humans then demonstrated two different ways to use the tool, one more efficient, one less efficient. Chimpanzees used the same efficient method following both demonstrations, regardless of what was demonstrated. Most of the human children, however, imitated whichever method the adult was demonstrating. If the chimps and humans were to be compared on the basis of these results, one might think that chimpanzees are more intelligent. From an

Linguists

Linguists

In the 19th century

In the 19th century

au/nowiki> and the meaning "cow", and a cultural sign, consisting for example of the cultural form of "wearing a crown" and the cultural meaning of "being king". In this way it can be argued that culture is itself a kind of language. Another parallel between cultural and linguistic systems is that they are both systems of practice, that is, they are a set of special ways of doing things that is constructed and perpetuated through social interactions. Children, for example, acquire language in the same way as they acquire the basic cultural norms of the society they grow up in – through interaction with older members of their cultural group.

However, languages, now understood as the particular set of speech norms of a particular community, are also a part of the larger culture of the community that speak them. Humans use language as a way of signalling identity with one cultural group and difference from others. Even among speakers of one language several different ways of using the language exist, and each is used to signal affiliation with particular subgroups within a larger culture. In linguistics such different ways of using the same language are called "

The modern anthropological concept of culture has its origins in the 19th century with German anthropologist

The modern anthropological concept of culture has its origins in the 19th century with German anthropologist

Boas's students dominated

Boas's students dominated  The second debate has been over the ability to make universal claims about all cultures. Although Boas argued that anthropologists had yet to collect enough solid evidence from a diverse sample of societies to make any valid general or universal claims about culture, by the 1940s some felt ready. Whereas Kroeber and Benedict had argued that "culture"—which could refer to local, regional, or trans-regional scales—was in some way "patterned" or "configured," some anthropologists now felt that enough data had been collected to demonstrate that it often took highly structured forms. The question these anthropologists debated was, were these structures statistical artifacts, or where they expressions of mental models? This debate emerged full-fledged in 1949, with the publication of

The second debate has been over the ability to make universal claims about all cultures. Although Boas argued that anthropologists had yet to collect enough solid evidence from a diverse sample of societies to make any valid general or universal claims about culture, by the 1940s some felt ready. Whereas Kroeber and Benedict had argued that "culture"—which could refer to local, regional, or trans-regional scales—was in some way "patterned" or "configured," some anthropologists now felt that enough data had been collected to demonstrate that it often took highly structured forms. The question these anthropologists debated was, were these structures statistical artifacts, or where they expressions of mental models? This debate emerged full-fledged in 1949, with the publication of

Parsons' students

Parsons' students

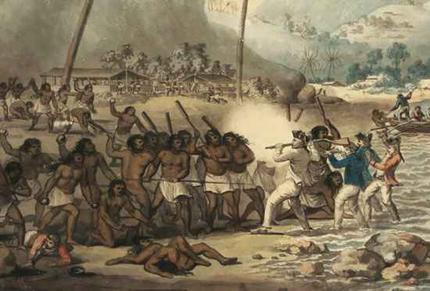

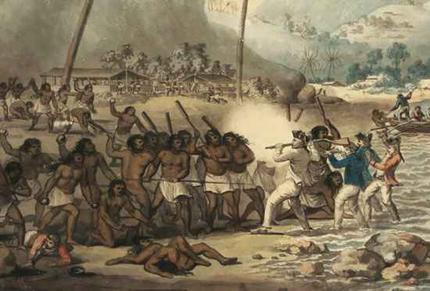

Boas and Malinowski established ethnographic research as a highly localized method for studying culture. Yet Boas emphasized that culture is dynamic, moving from one group of people to another, and that specific cultural forms have to be analyzed in a larger context. This has led anthropologists to explore different ways of understanding the global dimensions of culture.

In the 1940s and 1950s, several key studies focused on how trade between indigenous peoples and the Europeans who had conquered and colonized the Americas influenced indigenous culture, either through change in the organization of labor, or change in critical technologies. Bernard Mishkin studied the effect of the introduction of horses on

Boas and Malinowski established ethnographic research as a highly localized method for studying culture. Yet Boas emphasized that culture is dynamic, moving from one group of people to another, and that specific cultural forms have to be analyzed in a larger context. This has led anthropologists to explore different ways of understanding the global dimensions of culture.

In the 1940s and 1950s, several key studies focused on how trade between indigenous peoples and the Europeans who had conquered and colonized the Americas influenced indigenous culture, either through change in the organization of labor, or change in critical technologies. Bernard Mishkin studied the effect of the introduction of horses on

American anthropology has

American anthropology has culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

as its central and unifying concept. This most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode human experience

Experience refers to conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these conscious processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience involv ...

s symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

ically, and to communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially. American anthropology is organized into four fields, each of which plays an important role in research on culture:

# biological anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

# linguistic anthropology

Linguistic anthropology is the Interdisciplinarity, interdisciplinary study of how language influences social life. It is a branch of anthropology that originated from the endeavor to document endangered languages and has grown over the past cen ...

# cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The portma ...

# archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

Research in these fields has influenced anthropologists working in other countries to different degrees.

Biological anthropology

Discussion concerning culture among biological anthropologists centers around two debates. First, is culture uniquely human or shared by other species (most notably, other primates)? This is an important question, as the theory ofevolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

holds that humans are descended from (now extinct) non-human primates. Second, how did culture evolve among human beings?

Gerald Weiss noted that although Tylor's classic definition of culture was restricted to humans, many anthropologists take this for granted and thus elide that important qualification from later definitions, merely equating culture with any learned behavior. This slippage is a problem because during the formative years of modern primatology, some primatologists were trained in anthropology (and understood that culture refers to learned behavior among humans), and others were not. Notable non-anthropologists, like Robert Yerkes

Robert Mearns Yerkes (; May 26, 1876 – February 3, 1956) was an American psychologist, ethologist, eugenicist and primatologist best known for his work in intelligence testing and in the field of comparative psychology.

Yerkes was a pioneer ...

and Jane Goodall

Dame Jane Morris Goodall (; born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on 3 April 1934), formerly Baroness Jane van Lawick-Goodall, is an English primatologist and anthropologist. Seen as the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees, Goodall is best know ...

thus argued that since chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

s have learned behaviors, they have culture. Today, anthropological primatologists are divided, several arguing that non-human primates have culture, others arguing that they do not.

This scientific debate is complicated by ethical concerns. The subjects of primatology are non-human primates, and whatever culture these primates have is threatened by human activity. After reviewing the research on primate culture, W. C. McGrew concluded, " discipline requires subjects, and most species of nonhuman primates are endangered by their human cousins. Ultimately, whatever its merit, cultural primatology must be committed to cultural survival .e. to the survival of primate cultures"W. C. McGrew 1998 "Culture in Nonhuman Primates?" ''Annual Review of Anthropology'' 27: 323

McGrew suggests a definition of culture that he finds scientifically useful for studying primate culture. He points out that scientists do not have access to the subjective thoughts or knowledge of non-human primates. Thus, if culture is defined in terms of knowledge, then scientists are severely limited in their attempts to study primate culture. Instead of defining culture as a kind of knowledge, McGrew suggests that we view culture as a process. He lists six steps in the process:

# A new pattern of behavior is invented, or an existing one is modified.

# The innovator transmits this pattern to another.

# The form of the pattern is consistent within and across performers, perhaps even in terms of recognizable stylistic features.

# The one who acquires the pattern retains the ability to perform it long after having acquired it.

# The pattern spreads across social units in a population. These social units may be families, clans, troops, or bands.

# The pattern endures across generations.

McGrew admits that all six criteria may be strict, given the difficulties in observing primate behavior in the wild. But he also insists on the need to be as inclusive as possible, on the need for a definition of culture that "casts the net widely":

As Charles Frederick Voegelin pointed out, if "culture" is reduced to "learned behavior," then all animals have culture. Certainly all specialists agree that all primate species evidence common cognitive skills: knowledge of object-permanence, cognitive mapping, the ability to categorize objects, and creative problem solving. Moreover, all primate species show evidence of shared social skills: they recognize members of their social group; they form direct relationships based on degrees of kinship and rank; they recognize third-party social relationships; they predict future behavior; and they cooperate in problem-solving.

Human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

has been rapid with modern humans appearing about 340,000 years ago. During this time humanity evolved three distinctive features:

:(a) the creation and use of conventional symbols, including linguistic symbols and their derivatives, such as written language and mathematical symbols and notations; (b) the creation and use of complex tools and other instrumental technologies; and (c) the creation and participation in complex social organization and institutions. According to developmental psychologist

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of how and why humans grow, change, and adapt across the course of their lives. Originally concerned with infants and children, the field has expanded to include adolescence, adult development, ...

Michael Tomasello

Michael Tomasello (born January 18, 1950) is an American developmental and comparative psychologist, as well as a linguist. He is professor of psychology at Duke University.

Earning many prizes and awards from the end of the 1990s onward, he is c ...

, "where these complex and species-unique behavioral practices, and the cognitive skills that underlie them, came from" is a fundamental anthropological question. Given that contemporary humans and chimpanzees are far more different from horses and zebras, or rats and mice, and that the evolution of this great difference occurred in such a short period of time, "our search must be for some small difference that made a big difference – some adaptation, or small set of adaptations, that changed the process of primate cognitive evolution in fundamental ways." According to Tomasello, the answer to this question must form the basis of a scientific definition of "human culture."

In a recent review of the major research on human and primate tool-use, communication, and learning strategies, Tomasello argues that the key human advances over primates (language, complex technologies, and complex social organization) are all the results of humans pooling cognitive resources. This is called "the ratchet effect

A ratchet effect is an instance of the restrained ability of human processes to be reversed once a specific thing has happened, analogous with the mechanical ratchet that holds the spring tight as a clock is wound up. It is related to the phenom ...

:" innovations spread and are shared by a group, and mastered "by youngsters, which enables them to remain in their new and improved form within the group until something better comes along." The key point is that children are born good at a particular kind of social learning; this creates a favored environment for social innovations, making them more likely to be maintained and transmitted to new generations than individual innovations. For Tomasello, human social learning—the kind of learning that distinguishes humans from other primates and that played a decisive role in human evolution—is based on two elements: first, what he calls "imitative learning," (as opposed to " emulative learning" characteristic of other primates) and second, the fact that humans represent their experiences symbolically (rather than iconically, as is characteristic of other primates). Together, these elements enable humans to be both inventive, and to preserve useful inventions. It is this combination that produces the ratchet effect.

The kind of learning found among other primates is "emulation learning," which "focuses on the environmental events involved – results or changes of state in the environment that the other produced – rather than on the actions that produced those results."Michael Tomasello 1990 "Cultural Transmission in the Tool Use and Communicatory Signaling of Chimpanzees?" in ''"Language" and Intelligence in Monkeys and Apes: Comparative Developmental Perspectives'' ed. S. Parker, K. Bibson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 274–311 Tomasello emphasizes that emulation learning is a highly adaptive strategy for apes because it focuses on the effects of an act. In laboratory experiments, chimpanzees were shown two different ways for using a rake-like tool to obtain an out-of-reach-object. Both methods were effective, but one was more efficient than the other. Chimpanzees consistently emulated the more efficient method.Nagell, K., Olguin, K. and Tomasello, M. 1993 "Processes of social learning in the tool use of chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'') and human children (''Homo sapiens'')" in ''Journal of Comparative Psychology'' 107: 174–186

Examples of emulation learning are well documented among primates. Notable examples include Japanese

The kind of learning found among other primates is "emulation learning," which "focuses on the environmental events involved – results or changes of state in the environment that the other produced – rather than on the actions that produced those results."Michael Tomasello 1990 "Cultural Transmission in the Tool Use and Communicatory Signaling of Chimpanzees?" in ''"Language" and Intelligence in Monkeys and Apes: Comparative Developmental Perspectives'' ed. S. Parker, K. Bibson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 274–311 Tomasello emphasizes that emulation learning is a highly adaptive strategy for apes because it focuses on the effects of an act. In laboratory experiments, chimpanzees were shown two different ways for using a rake-like tool to obtain an out-of-reach-object. Both methods were effective, but one was more efficient than the other. Chimpanzees consistently emulated the more efficient method.Nagell, K., Olguin, K. and Tomasello, M. 1993 "Processes of social learning in the tool use of chimpanzees (''Pan troglodytes'') and human children (''Homo sapiens'')" in ''Journal of Comparative Psychology'' 107: 174–186

Examples of emulation learning are well documented among primates. Notable examples include Japanese macaque

The macaques () constitute a genus (''Macaca'') of gregarious Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae. The 23 species of macaques inhabit ranges throughout Asia, North Africa, and (in one instance) Gibraltar. Macaques are principally ...

potato washing, chimpanzee tool use, and chimpanzee gestural communication. In 1953, an 18-month-old female macaque monkey was observed taking sandy pieces of sweet potato (given to the monkeys by observers) to a stream (and later, to the ocean) to wash off the sand. After three months, the same behavior was observed in her mother and two playmates, and then the playmates' mothers. Over the next two years seven other young macaques were observed washing their potatoes, and by the end of the third year 40% of the troop had adopted the practice.M. Kawai 1965 "Newly acquired pre-cultural behavior of the natural troop of Japanese monkeys on Koshima Islet" ''Primates'' 6: 1–30 Although this story is popularly represented as a straightforward example of human-like learning, evidence suggests that it is not. Many monkeys naturally brush sand off food; this behavior had been observed in the macaque troop prior to the first observed washing. Moreover, potato washing was observed in four other separate macaque troops, suggesting that at least four other individual monkeys had learned to wash off sand on their own. Other monkey species in captivity quickly learn to wash off their food. Finally, the spread of learning among the Japanese macaques was fairly slow, and the rate at which new members of the troop learned did not keep pace with the growth of the troop. If the form of learning were imitation, the rate of learning should have been exponential. It is more likely that the monkeys' washing behavior is based on the common behavior of cleaning off food, and that monkeys that spent time by the water independently learned to wash, rather than wipe their food. This explains both why those monkeys that kept company with the original washer, and who thus spent a good deal of time by the water, also figured out how to wash their potatoes. It also explains why the rate at which this behavior spread was slow.

Chimpanzees exhibit a variety of population-specific tool use: termite-fishing, ant-fishing, ant-dipping, nut-cracking, and leaf-sponging. Gombe Chimpanzees fish for termites using small, thin sticks, but chimpanzees in Western Africa use large sticks to break holes in mounds and use their hands to scoop up termites. Some of this variation may be the result of "environmental shaping" (there is more rainfall in western Africa, softening termite mounds and making them easier to break apart, than in the Gombe reserve in eastern Africa). Nevertheless, it is clear that chimpanzees are good at emulation learning. Chimpanzee children independently know how to roll over logs, and know how to eat insects. When children see their mothers rolling over logs to eat the insects beneath, they quickly learn to do the same. In other words, this form of learning builds on activities the children already know.

The kind of learning characteristic of human children is imitative learning, which "means reproducing an instrumental act understood intentionally." Human infants begin to display some evidence of this form of learning between the ages of nine and 12 months, when infants fix their attention not only on an object, but on the gaze of an adult which enables them to use adults as points of reference and thus "act on objects in the way adults are acting on them." This dynamic is well documented and has also been termed "joint engagement" or "joint attention." Essential to this dynamic is the infant's growing capacity to recognize others as "intentional agents:" people "with the power to control their spontaneous behavior" and who "have goals and make active choices among behavioral means for attaining those goals."

The development of skills in joint attention by the end of a human child's first year of life provides the basis for the development of imitative learning in the second year. In one study 14-month-old children imitated an adult's over-complex method of turning on a light, even when they could have used an easier and more natural motion to the same effect. In another study, 16-month-old children interacted with adults who alternated between a complex series of motions that appeared intentional and a comparable set of motions that appeared accidental; they imitated only those motions that appeared intentional. Another study of 18-month old children revealed that children imitate actions that adults intend, yet in some way fail, to perform.

Tomasello emphasizes that this kind of imitative learning "relies fundamentally on infants' tendency to identify with adults, and on their ability to distinguish in the actions of others the underlying goal and the different means that might be used to achieve it." He calls this kind of imitative learning "cultural learning because the child is not just learning about things from other persons, she is also learning things through them — in the sense that she must know something of the adult's perspective on a situation to learn the active use of this same intentional act." He concludes that the key feature of cultural learning is that it occurs only when an individual "understands others as intentional agents, like the self, who have a perspective on the world that can be followed into, directed and shared."

Emulation learning and imitative learning are two different adaptations that can only be assessed in their larger environmental and evolutionary contexts. In one experiment, chimpanzees and two-year-old children were separately presented with a rake-like-tool and an out-of-reach object. Adult humans then demonstrated two different ways to use the tool, one more efficient, one less efficient. Chimpanzees used the same efficient method following both demonstrations, regardless of what was demonstrated. Most of the human children, however, imitated whichever method the adult was demonstrating. If the chimps and humans were to be compared on the basis of these results, one might think that chimpanzees are more intelligent. From an

The kind of learning characteristic of human children is imitative learning, which "means reproducing an instrumental act understood intentionally." Human infants begin to display some evidence of this form of learning between the ages of nine and 12 months, when infants fix their attention not only on an object, but on the gaze of an adult which enables them to use adults as points of reference and thus "act on objects in the way adults are acting on them." This dynamic is well documented and has also been termed "joint engagement" or "joint attention." Essential to this dynamic is the infant's growing capacity to recognize others as "intentional agents:" people "with the power to control their spontaneous behavior" and who "have goals and make active choices among behavioral means for attaining those goals."

The development of skills in joint attention by the end of a human child's first year of life provides the basis for the development of imitative learning in the second year. In one study 14-month-old children imitated an adult's over-complex method of turning on a light, even when they could have used an easier and more natural motion to the same effect. In another study, 16-month-old children interacted with adults who alternated between a complex series of motions that appeared intentional and a comparable set of motions that appeared accidental; they imitated only those motions that appeared intentional. Another study of 18-month old children revealed that children imitate actions that adults intend, yet in some way fail, to perform.

Tomasello emphasizes that this kind of imitative learning "relies fundamentally on infants' tendency to identify with adults, and on their ability to distinguish in the actions of others the underlying goal and the different means that might be used to achieve it." He calls this kind of imitative learning "cultural learning because the child is not just learning about things from other persons, she is also learning things through them — in the sense that she must know something of the adult's perspective on a situation to learn the active use of this same intentional act." He concludes that the key feature of cultural learning is that it occurs only when an individual "understands others as intentional agents, like the self, who have a perspective on the world that can be followed into, directed and shared."

Emulation learning and imitative learning are two different adaptations that can only be assessed in their larger environmental and evolutionary contexts. In one experiment, chimpanzees and two-year-old children were separately presented with a rake-like-tool and an out-of-reach object. Adult humans then demonstrated two different ways to use the tool, one more efficient, one less efficient. Chimpanzees used the same efficient method following both demonstrations, regardless of what was demonstrated. Most of the human children, however, imitated whichever method the adult was demonstrating. If the chimps and humans were to be compared on the basis of these results, one might think that chimpanzees are more intelligent. From an evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary perspective they are equally intelligent, but with different kinds of intelligence adapted to different environments. Chimpanzee learning strategies are well-suited to a stable physical environment that requires little social cooperation (compared to humans). Human learning strategies are well-suited to a more complex social environment in which understanding the intentions of others may be more important than success at a specific task. Tomasello argues that this strategy has made possible the "ratchet effect" that enabled humans to evolve complex social systems that have enabled humans to adapt to virtually every physical environment on the surface of the earth.

Tomasello further argues that cultural learning is essential for language-acquisition. Most children in any society, and all children in some, do not learn all words through the direct efforts of adults. "In general, for the vast majority of words in their language, children must find a way to learn in the ongoing flow of social interaction, sometimes from speech not even addressed to them." This finding has been confirmed by a variety of experiments in which children learned words even when the referent was not present, multiple referents were possible, and the adult was not directly trying to teach the word to the child. Tomasello concludes that "a linguistic symbol is nothing other than a marker for an intersubjectively shared understanding of a situation."

Tomasello's 1999 review of the research contrasting human and non-human primate learning strategies confirms biological anthropologist

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

Ralph Holloway Ralph Leslie Holloway, Jr. (born 1935) is a physical anthropologist at Columbia University and research associate with the American Museum of Natural History. Since obtaining his Ph.D from the University of California, Berkeley in 1964, Holloway ha ...

's 1969 argument that a specific kind of sociality linked to symbolic cognition were the keys to human evolution, and constitute the nature of culture. According to Holloway, the key issue in the evolution of ''H. sapiens'', and the key to understanding "culture," "is how man organizes his experience." Culture is "the ''imposition of arbitrary form upon the environment.''" This fact, Holloway argued, is primary to and explains what is distinctive about human learning strategies, tool-use, and language. Human tool-making and language express "similar, if not identical, cognitive processes" and provide important evidence for how humankind evolved.

In other words, whereas McGrew argues that anthropologists must focus on behaviors like communication and tool-use because they have no access to the mind, Holloway argues that human language and tool-use, including the earliest stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s in the fossil record 2.6 million years ago, are highly suggestive of cognitive differences between humans and non-humans, and that such cognitive differences in turn explain human evolution. For Holloway, the question is not ''whether'' other primates communicate, learn or make tools, but the ''way'' they do these things. "Washing potatoes in the ocean ... stripping branches of leaves to get termites," and other examples of primate tool-use and learning "are iconic, and there is no feedback from the environment to the animal." Human tools, however, express an independence from natural form that manifests symbolic thinking. "In the preparation of the stick for termite-eating, the relation between product and raw material is iconic. In the making of a stone tool, in contrast, there is no necessary relation between the form of the final product and the original material."

In Holloway's view, our non-human ancestors, like those of modern chimpanzees and other primates, shared motor and sensory skills, curiosity, memory, and intelligence, with perhaps differences in degree. He adds: "It is when these are integrated with the unique attributes of arbitrary production (symbolization) and imposition that man qua cultural man appears."

He also adds:

This is comparable to the "ratcheting" aspect suggested by Tomasello and others that enabled human evolution to accelerate. Holloway concludes that the first instance of symbolic thought among humans provided a "kick-start" for brain development, tool complexity, social structure, and language to evolve through a constant dynamic of positive feedback. "This interaction between the propensity to structure the environment arbitrarily and the feedback from the environment to the organism is an emergent process, a process different in kind from anything that preceded it."

Linguists

Linguists Charles Hockett

Charles Francis Hockett (January 17, 1916 – November 3, 2000) was an American linguist who developed many influential ideas in American structuralism#Structuralism in linguistics, structuralist linguistics. He represents the post-Leonard Bloomfi ...

and R. Ascher have identified thirteen design-features of language, some shared by other forms of animal communication. One feature that distinguishes human language is its tremendous productivity; in other words, competent speakers of a language are capable of producing an exponential number of original utterances. This productivity seems to be made possible by a few critical features unique to human language. One is "duality of patterning," meaning that human language consists of the articulation of several distinct processes, each with its own set of rules: combining phonemes

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-west o ...

to produce morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest meaningful constituent of a linguistic expression. The field of linguistic study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology.

In English, morphemes are often but not necessarily words. Morphemes that stand alone a ...

, combining morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest meaningful constituent of a linguistic expression. The field of linguistic study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology.

In English, morphemes are often but not necessarily words. Morphemes that stand alone a ...

to produce words, and combining words to produce sentences. This means that a person can master a relatively limited number of signals and sets of rules, to create infinite combinations. Another crucial element is that human language is symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

ic: the sound of words (or their shape, when written) typically bear no relation to what they represent. In other words, their meaning is arbitrary. That words have meaning is a matter of convention. Since the meaning of words are arbitrary, any word may have several meanings, and any object may be referred to using a variety of words; the actual word used to describe a particular object depends on the context, the intention of the speaker, and the ability of the listener to judge these appropriately. As Tomasello notes,

Holloway argues that the stone tools associated with genus ''Homo'' have the same features of human language:

He also adds:

As Tomasello demonstrates, symbolic thought can operate only in a particular social environment:

Biological anthropologist

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

Terrence Deacon, in a synthesis of over twenty years of research on human evolution, human neurology, and primatology, describes this "ratcheting effect" as a form of "Baldwinian Evolution." Named after psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and interpretation of how indi ...

James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; de ...

, this describes a situation in which an animal's behavior has evolutionary consequences when it changes the natural environment and thus the selective forces acting on the animal.

According to Deacon, this occurred between 2 and 2.5 million years ago, when we have the first fossil evidence of stone tool use and the beginning of a trend in an increase in brain size. But it is the evolution of symbolic language which is the cause—and not the effect—of these trends. More specifically, Deacon is suggesting that ''Australopithecines'', like contemporary apes, used tools; it is possible that over the millions of years of ''Australopithecine'' history, many troops developed symbolic communication systems. All that was necessary was that one of these groups so altered their environment that "it introduced selection for very different learning abilities than affected prior species." This troop or population kick-started the Baldwinian process (the "ratchet effect") that led to their evolution to genus ''Homo''.

The question for Deacon is what behavioral-environmental changes could have made the development of symbolic thinking adaptive? Here he emphasizes the importance of distinguishing humans from all other species, not to privilege human intelligence but to problematize it. Given that the evolution of ''H. sapiens'' began with ancestors who did not yet have "culture," what led them to move away from cognitive, learning, communication, and tool-making strategies that were and continued to be adaptive for most other primates (and, some have suggested, most other species of animals)? Learning symbol systems is more time-consuming than other forms of communication, so symbolic thought made possible a different communication strategy, but not a more efficient one than other primates. Nevertheless, it must have offered some selective advantage to ''H. sapiens'' to have evolved. Deacon starts by looking at two key determinants in evolutionary history: foraging behavior, and patterns of sexual relations. As he observes competition for sexual access limits the possibilities for social cooperation in many species; yet, Deacon observes, there are three consistent patterns in human reproduction that distinguish them from other species:

# Both males and females usually contribute effort towards the rearing of their offspring, though often to differing extents and in very different ways.

# In all societies, the great majority of adult males and females are bound by long-term, exclusive sexual access rights and prohibitions to particular individuals of the opposite sex.

# They maintain these exclusive sexual relations while living in modest to large-sized, multi-male, multi-female, cooperative social groups.

Moreover, there is one feature common to all known human foraging societies (all humans prior to ten or fifteen thousand years ago), and markedly different from other primates: "the use of meat... . The appearance of the first stone tools nearly 2.5 million years ago almost certainly correlates with a radical shift in foraging behavior to gain access to meat." Deacon does not believe that symbolic thought was necessary for hunting or tool-making (although tool-making may be a reliable index of symbolic thought); rather, it was necessary for the success of distinctive social relations.

The key is that while men and women are equally effective foragers, mothers carrying dependent children are not effective hunters. They must thus depend on male hunters. This favors a system in which males have exclusive sexual access to females, and females can predict that their sexual partner will provide food for them and their children. In most mammalian species the result is a system of rank or sexual competition that results in either polygyny, or lifelong pair-bonding between two individuals who live relatively independent of other adults of their species; in both cases male aggression plays an important role in maintaining sexual access to mate(s).

What is uniquely characteristic about human societies is what required symbolic cognition, which consequently leads to the evolution of culture: "cooperative, mixed-sex social groups, with significant male care and provisioning of offspring, and relatively stable patterns of reproductive exclusion." This combination is relatively rare in other species because it is "highly susceptible to disintegration." Language and culture provide the glue that holds it together.

Chimpanzees also, on occasion, hunt meat; in most cases, however, males consume the meat immediately, and only on occasion share with females who happen to be nearby. Among chimpanzees, hunting for meat increases when other sources of food become scarce, but under these conditions sharing decreases. The first forms of symbolic thinking made stone tools possible, which in turn made hunting for meat a more dependable source of food for our nonhuman ancestors while making possible forms of social communication that make sharing between males and females, but also among males, decreasing sexual competition:

Symbols and symbolic thinking thus make possible a central feature of social relations in every human population: reciprocity. Evolutionary scientists have developed a model to explain reciprocal altruism

In evolutionary biology, reciprocal altruism is a behaviour whereby an organism acts in a manner that temporarily reduces its fitness while increasing another organism's fitness, with the expectation that the other organism will act in a similar m ...

among closely related individuals. Symbolic thought makes possible reciprocity between distantly related individuals.

Archaeology

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

was often a supplement to history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

, and the goal of archaeologists was to identify artifacts according to their typology

Typology is the study of types or the systematic classification of the types of something according to their common characteristics. Typology is the act of finding, counting and classification facts with the help of eyes, other senses and logic. Ty ...

and stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock (geology), rock layers (Stratum, strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary rock, sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigrap ...

, thus marking their location in time and space. Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

established that archaeology be one of American anthropology's four fields, and debates among archaeologists have often paralleled debates among cultural anthropologists. In the 1920s and 1930s, Australian-British archaeologist V. Gordon Childe

Vere Gordon Childe (14 April 189219 October 1957) was an Australian archaeologist who specialised in the study of European prehistory. He spent most of his life in the United Kingdom, working as an academic for the University of Edinburgh and th ...

and American archaeologist W. C. McKern independently began moving from asking about the date of an artifact, to asking about the people who produced it – when archaeologists work alongside historians, historical materials generally help answer these questions, but when historical materials are unavailable, archaeologists had to develop new methods. Childe and McKern focused on analyzing the relationships among objects found together; their work established the foundation for a three-tiered model:

# An individual artifact, which has surface, shape, and technological attributes (e.g. an arrowhead)

# A sub-assemblage, consisting of artifacts that are found, and were likely used, together (e.g. an arrowhead, bow and knife)

# An assemblage of sub-assemblages that together constitute the archaeological site (e.g. the arrowhead, bow and knife; a pot and the remains of a hearth; a shelter)

Childe argued that a "constantly recurring assemblage of artifacts" is an "archaeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

." Childe and others viewed "each archaeological culture ... the manifestation in material terms of a specific ''people''."

In 1948, Walter Taylor systematized the methods and concepts that archaeologists had developed and proposed a general model for the archaeological contribution to knowledge of cultures. He began with the mainstream understanding of culture as the product of human cognitive activity, and the Boasian emphasis on the subjective meanings of objects as dependent on their cultural context. He defined culture as "a mental phenomenon, consisting of the contents of minds, not of material objects or observable behavior." He then devised a three-tiered model linking cultural anthropology to archeology, which he called conjunctive archaeology:

# Culture, which is unobservable (behavior) and nonmaterial

# Behaviors resulting from culture, which are observable and nonmaterial

# Objectifications, such as artifacts and architecture, which are the result of behavior and material

That is, material artifacts were the material residue of culture, but not culture itself. Taylor's point was that the archaeological record could contribute to anthropological knowledge, but only if archaeologists reconceived their work not just as digging up artifacts and recording their location in time and space, but as inferring from material remains the behaviors through which they were produced and used, and inferring from these behaviors the mental activities of people. Although many archaeologists agreed that their research was integral to anthropology, Taylor's program was never fully implemented. One reason was that his three-tier model of inferences required too much fieldwork and laboratory analysis to be practical. Moreover, his view that material remains were not themselves cultural, and in fact twice-removed from culture, in fact left archaeology marginal to cultural anthropology.

In 1962, Leslie White's former student Lewis Binford

Lewis Roberts Binford (November 21, 1931 – April 11, 2011) was an American archaeologist known for his influential work in archaeological theory, ethnoarchaeology and the Paleolithic period. He is widely considered among the most influe ...

proposed a new model for anthropological archaeology, called "the New Archaeology" or "Processual Archaeology

Processual archaeology (formerly, the New Archaeology) is a form of archaeological theory that had its beginnings in 1958 with the work of Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips, ''Method and Theory in American Archaeology,'' in which the pair stated ...

," based on White's definition of culture as "the extra-somatic means of adaptation for the human organism." This definition allowed Binford to establish archaeology as a crucial field for the pursuit of the methodology of Julian Steward's cultural ecology:

In other words, Binford proposed an archaeology that would be central to the dominant project of cultural anthropologists at the time (culture as non-genetic adaptations to the environment); the "new archaeology" was the cultural anthropology (in the form of cultural ecology or ecological anthropology) of the past.

In the 1980s, there was a movement in the United Kingdom and Europe against the view of archeology as a field of anthropology, echoing Radcliffe-Brown's earlier rejection of cultural anthropology. During this same period, then-Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

archaeologist Ian Hodder

Ian Richard Hodder (born 23 November 1948, in Bristol) is a British archaeologist and pioneer of postprocessualist theory in archaeology that first took root among his students and in his own work between 1980–1990. At this time he had such ...

developed "post-processual archaeology

Post-processual archaeology, which is sometimes alternately referred to as the interpretative archaeologies by its adherents, is a movement in archaeological theory that emphasizes the subjectivity of archaeological interpretations. Despite having ...

" as an alternative. Like Binford (and unlike Taylor) Hodder views artifacts not as objectifications of culture but ''as'' culture itself. Unlike Binford, however, Hodder does not view culture as an environmental adaptation. Instead, he "is committed to a fluid semiotic version of the traditional culture concept in which material items, artifacts, are full participants in the creation, deployment, alteration, and fading away of symbolic complexes." His 1982 book, ''Symbols in Action'', evokes the symbolic anthropology of Geertz, Schneider, with their focus on the context dependent meanings of cultural things, as an alternative to White and Steward's materialist view of culture. In his 1991 textbook, ''Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology'' Hodder argued that archaeology is more closely aligned to history than to anthropology.

Linguistic anthropology

The connection between culture and language has been noted as far back as the classical period and probably long before. The ancient Greeks, for example, distinguished between civilized peoples and bárbaroi "those who babble", i.e. those who speak unintelligible languages. The fact that different groups speak different, unintelligible languages is often considered more tangible evidence for cultural differences than other less obvious cultural traits. The German romanticists of the 19th century such asJohann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

and Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (, also , ; ; 22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a Prussian philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin, which was named after ...

, often saw language not just as one cultural trait among many but rather as the direct expression of a people's national character, and as such as culture in a kind of condensed form. Herder for example suggests, "''Denn jedes Volk ist Volk; es hat seine National Bildung wie seine Sprache''" (Since every people is a People, it has its own national culture expressed through its own language).

Franz Boas, founder of American anthropology, like his German forerunners, maintained that the shared language of a community is the most essential carrier of their common culture. Boas was the first anthropologist who considered it unimaginable to study the culture of a foreign people without also becoming acquainted with their language. For Boas, the fact that the intellectual culture of a people was largely constructed, shared and maintained through the use of language, meant that understanding the language of a cultural group was the key to understanding its culture. At the same time, though, Boas and his students were aware that culture and language are not directly dependent on one another. That is, groups with widely different cultures may share a common language, and speakers of completely unrelated languages may share the same fundamental cultural traits. Numerous other scholars have suggested that the form of language determines specific cultural traits. This is similar to the notion of linguistic determinism

Linguistic determinism is the concept that language and its structures limit and determine human knowledge or thought, as well as thought processes such as categorization, memory, and perception. The term implies that people's native languages wil ...

, which states that the form of language determines individual thought. While Boas himself rejected a causal link between language and culture, some of his intellectual heirs entertained the idea that habitual patterns of speaking and thinking in a particular language may influence the culture of the linguistic group. Such belief is related to the theory of linguistic relativity

The hypothesis of linguistic relativity, also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis , the Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism, is a principle suggesting that the structure of a language affects its speakers' world view, worldview or cognition, and ...

. Boas, like most modern anthropologists, however, was more inclined to relate the interconnectedness between language and culture to the fact that, as B.L. Whorf put it, "they have grown up together".

Indeed, the origin of language

The origin of language (spoken and signed, as well as language-related technological systems such as writing), its relationship with human evolution, and its consequences have been subjects of study for centuries. Scholars wishing to study th ...

, understood as the human capacity of complex symbolic communication, and the origin of complex culture is often thought to stem from the same evolutionary process in early man. Evolutionary anthropologist Robin I. Dunbar has proposed that language evolved as early humans began to live in large communities which required the use of complex communication to maintain social coherence. Language and culture then both emerged as a means of using symbols to construct social identity and maintain coherence within a social group too large to rely exclusively on pre-human ways of building community such as for example grooming. Since language and culture are both in essence symbolic systems, twentieth century cultural theorists have applied the methods of analyzing language developed in the science of linguistics to also analyze culture. Particularly the structural

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such a ...

theory of Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure (; ; 26 November 1857 – 22 February 1913) was a Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher. His ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in both linguistics and semiotics in the 20th century. He is widel ...

which describes symbolic systems as consisting of signs (a pairing of a particular form with a particular meaning) has come to be applied widely in the study of culture. But also post-structuralist theories that nonetheless still rely on the parallel between language and culture as systems of symbolic communication, have been applied in the field of semiotics

Semiotics (also called semiotic studies) is the systematic study of sign processes ( semiosis) and meaning making. Semiosis is any activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, where a sign is defined as anything that communicates something ...

. The parallel between language and culture can then be understood as analog to the parallel between a linguistic sign, consisting for example of the sound varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

". For example, the English language is spoken differently in the US, the UK and Australia, and even within English-speaking countries there are hundreds of dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of Linguistics, linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety (linguisti ...

s of English that each signals a belonging to a particular region and/or subculture. For example, in the UK the cockney

Cockney is an accent and dialect of English, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by working-class and lower middle-class Londoners. The term "Cockney" has traditionally been used to describe a person from the East End, or b ...

dialect signals its speakers' belonging to the group of lower class workers of east London. Differences between varieties of the same language often consist in different pronunciations and vocabulary, but also sometimes of different grammatical systems and very often in using different styles (e.g. cockney rhyming slang

Rhyming slang is a form of slang word construction in the English language. It is especially prevalent among Cockneys in England, and was first used in the early 19th century in the East End of London; hence its alternative name, Cockney rhymin ...

or lawyers' jargon). Linguists and anthropologists, particularly sociolinguists

Sociolinguistics is the descriptive study of the effect of any or all aspects of society, including cultural norms, expectations, and context, on the way language is used, and society's effect on language. It can overlap with the sociology of l ...

, ethnolinguists and linguistic anthropologists have specialized in studying how ways of speaking vary between speech communities.

A community's ways of speaking or signing are a part of the community's culture, just as other shared practices are. Language use is a way of establishing and displaying group identity. Ways of speaking function not only to facilitate communication, but also to identify the social position of the speaker. Linguists call different ways of speaking language varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

, a term that encompasses geographically or socioculturally defined dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of Linguistics, linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety (linguisti ...

s as well as the jargons or styles of subculture

A subculture is a group of people within a culture that differentiates itself from the parent culture to which it belongs, often maintaining some of its founding principles. Subcultures develop their own norms and values regarding cultural, poli ...

s. Linguistic anthropologists and sociologists of language define communicative style as the ways that language is used and understood within a particular culture.

The difference between languages does not consist only in differences in pronunciation, vocabulary or grammar, but also in different "cultures of speaking". Some cultures for example have elaborate systems of "social deixis", systems of signalling social distance through linguistic means.Foley 1997 p?? In English, social deixis is shown mostly though distinguishing between addressing some people by first name and others by surname, but also in titles such as "Mrs.", "boy", "Doctor" or "Your Honor", but in other languages such systems may be highly complex and codified in the entire grammar and vocabulary of the language. In several languages of east Asia, for example Thai

Thai or THAI may refer to:

* Of or from Thailand, a country in Southeast Asia

** Thai people, the dominant ethnic group of Thailand

** Thai language, a Tai-Kadai language spoken mainly in and around Thailand

*** Thai script

*** Thai (Unicode block ...

, Burmese

Burmese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Myanmar, a country in Southeast Asia

* Burmese people

* Burmese language

* Burmese alphabet

* Burmese cuisine

* Burmese culture

Animals

* Burmese cat

* Burmese chicken

* Burmese (hor ...

and Javanese, different words are used according to whether a speaker is addressing someone of higher or lower rank than oneself in a ranking system with animals and children ranking the lowest and gods and members of royalty as the highest. Other languages may use different forms of address when speaking to speakers of the opposite gender or in-law relatives and many languages have special ways of speaking to infants and children. Among other groups, the culture of speaking may entail ''not speaking'' to particular people, for example many indigenous cultures of Australia have a taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

against talking to one's in-law relatives, and in some cultures speech is not addressed directly to children. Some languages also require different ways of speaking for different social classes of speakers, and often such a system is based on gender differences, as in Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

and Koasati

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the territor ...

.

Cultural anthropology

Universal versus particular

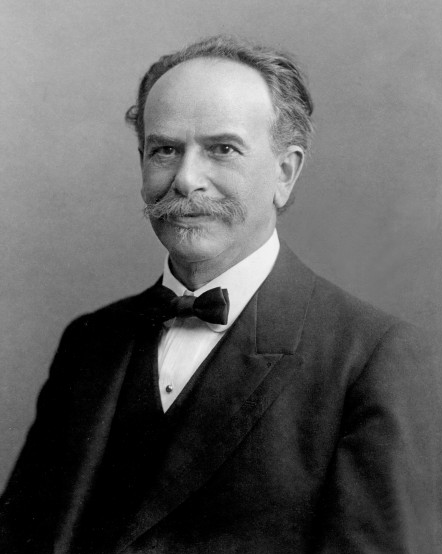

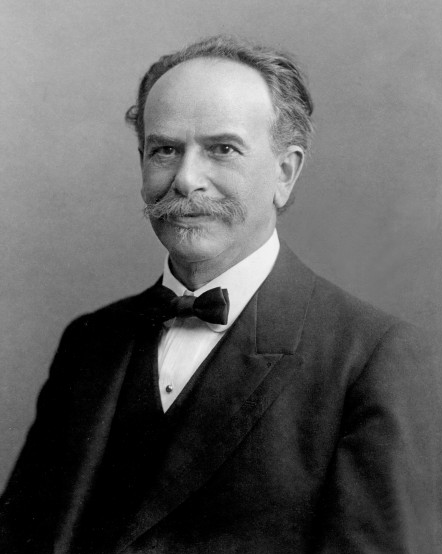

The modern anthropological concept of culture has its origins in the 19th century with German anthropologist

The modern anthropological concept of culture has its origins in the 19th century with German anthropologist Adolf Bastian

Adolf Philipp Wilhelm Bastian (26 June 18262 February 1905) was a 19th-century polymath best remembered for his contributions to the development of ethnography and the development of anthropology as a discipline. Modern psychology owes him a great ...

's theory of the "psychic unity of mankind," which, influenced by Herder and von Humboldt, challenged the identification of "culture" with the way of life of European elites, and British anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (2 October 18322 January 1917) was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.

Tylor's ideas typify 19th-century cultural evolutionism. In his works '' Primitive Culture'' (1871) and ''Anthropology'' ...

's attempt to define culture as inclusively as possible. Tylor in 1874 described culture in the following way: "Culture or civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

, taken in its wide ethnographic

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society." Although Tylor was not aiming to propose a general theory of culture (he explained his understanding of culture in the course of a larger argument about the nature of religion), American anthropologists have generally presented their various definitions of culture as refinements of Tylor's. Franz Boas's student Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

(1876–1970) identified culture with the "superorganic," that is, a domain with ordering principles and laws that could not be explained by or reduced to biology. In 1973, Gerald Weiss reviewed various definitions of culture and debates as to their parsimony and power, and proposed as the most scientifically useful definition that "culture" be defined "''as our generic term for all human nongenetic, or metabiological, phenomena''" (italics in the original).

Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

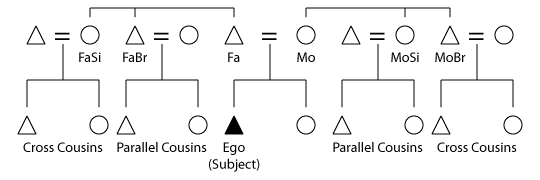

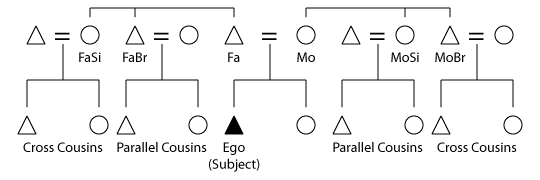

founded modern American anthropology with the establishment of the first graduate program in anthropology at Columbia University in 1896. At the time the dominant model of culture was that of cultural evolution

Cultural evolution is an evolutionary theory of social change. It follows from the definition of culture as "information capable of affecting individuals' behavior that they acquire from other members of their species through teaching, imitation a ...

, which posited that human societies progressed through stages of savagery to barbarism to civilization; thus, societies that for example are based on horticulture and Iroquois kinship

Iroquois kinship (also known as bifurcate merging) is a kinship system named after the Haudenosaunee people, also known as the ''Iroquois'', whose kinship system was the first one described to use this particular type of system. Identified by Le ...

terminology are less evolved than societies based on agriculture and Eskimo kinship

Eskimo kinship or Inuit kinship is a category of kinship used to define family organization in anthropology. Identified by Lewis Henry Morgan in his 1871 work ''Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family'', the Eskimo system was o ...

terminology. One of Boas's greatest accomplishments was to demonstrate convincingly that this model is fundamentally flawed, empirically, methodologically, and theoretically. Moreover, he felt that our knowledge of different cultures was so incomplete, and often based on unsystematic or unscientific research, that it was impossible to develop any scientifically valid general model of human cultures. Instead, he established the principle of cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the idea that a person's beliefs and practices should be understood based on that person's own culture. Proponents of cultural relativism also tend to argue that the norms and values of one culture should not be evaluated ...

and trained students to conduct rigorous participant observation

Participant observation is one type of data collection method by practitioner-scholars typically used in qualitative research and ethnography. This type of methodology is employed in many disciplines, particularly anthropology (incl. cultural an ...